Is an approach to economic, political and spatial implications about the definitions of the public/ private space that “Mean Hight Water Mark” (MHWM) establishes.

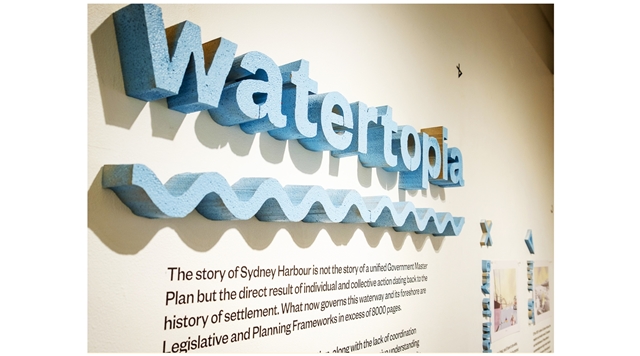

The story of Sydney Harbour is not the story of a unified Government Master Plan but the direct result of individual and collective action dating back to the history of settlement. What now governs this waterway and its foreshore is in excess of 8000 pages of Local, State and Federal Acts, Regulations, Development Control Plans, Local Environment Plans, Guides, Crown Notations and Freehold Titles, Protections, Development Manuals, Statuary Requirements, Policies, Legislation, Master Plans, and Strategic Frameworks.

This complexity and fragmentation, along with the lack of coordination of the different authorities, prevents a comprehensive understanding of this land.

Public space in the foreshore is one of the main victims: its access and use is in danger through both privatization and capitalization, being this labyrinth of laws and authorities the perfect accomplice.

Watertopia is a proposal for the future use of Sydney Harbour, by reframing the existing infrastructure with a contemporary social and cultural agenda. While building new infrastructure is crucial for any city, how could the simple act of changing existing rules-of-use allow for low impact economies to emerge and allow for a more accessible and contemporary public space on the foreshore?

In the tradition of the 1986 PAN EUROPEAN PICNIC performance, we try to answer the question of Otto von Hamsburg: What would Europe be without borders? What would Sydney Harbour be if the ‘un-public’ became public?

Here we present a proposal to change the Rules-of-Use for 5 simple, but instrumental pieces of Sydney Harbour infrastructure.

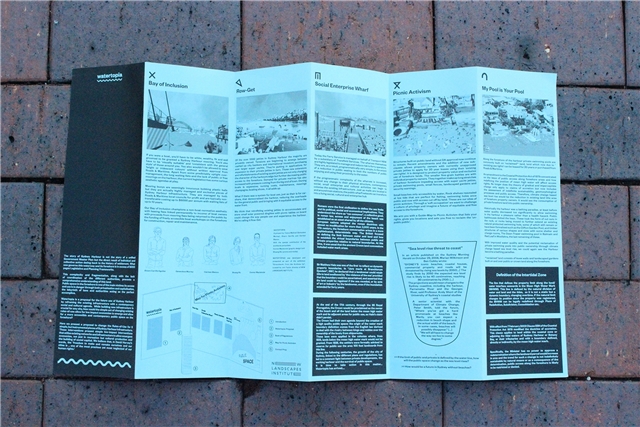

Bay of Inclusion

If you were a boat, you’d have to be white, wealthy, fit and well groomed to be granted a Sydney Harbour mooring. You’d also have to be ‘visually suitable’ and ‘consistent with the general style’ of those around you. You also wouldn’t be allowed to wear ‘bright or iridescent colours’ without written approval from Roads & Maritime. Apart from some predictably uptight over-management, the long waiting lists and the lack of public or free moorings on the harbour, the current legislation has some curious aesthetic agendas at play.

Mooring buoys are seemingly innocuous bobbing plastic balls but they are actually highly managed and exclusive pieces of Sydney Harbour infrastructure. They are managed by both Roads & Maritime and local councils for profit and are typically non transferable costing up to $6000 per annum with waiting lists of up to 10 years.

Our Bay of Inclusion champions a non-boat normative aesthetic with leasing fees linked permanently to income of boat owners with proceeds from mooring fees being returned to the public by the funding of freely accessible boat workshops on the foreshore for construction, repair and maintenance.

Row- Get

Of the over 1000 jetties in Sydney Harbour the majority are privately owned. Tensions are beginning to emerge between cashed up city bankers and international investors purchasing ever larger super yachts. They’re putting in applications for expansion to their private jetties in turn. These new extensions and refurbishments of existing quaint jetties are not only changing the character of the harbours edge but further decreasing public access to the foreshore. Demand for private marinas has also increased with pressure coming from the big end of town. Owning boats is expensive; running costs, maintenance, moorings champagne, boating shoes.. it all adds up. What if there was a system for boat use, just as there is for car-share, that democratised

the harbour, reducing the overheads for the general public and bringing with it equitable access to the water front? We think that retrofitting existing jetties to accommodate and store small solar powered dinghies with picnic tables on board could change the way people use and experience the harbour. We’re calling it Row-Get.

Social Enterprise Wharf

Today the Ferry Service is managed on behalf of Transport NSW by a subsidiary of Transfield Services. The wharves themselves are highly legislated to manage and reduce risk to ferry operators. They are, as a result, programmatically very simple, to the extent of a reduction in public seating to limit the numbers of public enjoying and using their proximity to the water. If the programmatic complexity of the wharves is increased, without any change to their physical structure, contemporary social, small enterprise and cultural activities can begin to colonise the existing infrastructure. Just as malls are located in and around train stations, the public wharf network can transform into a living social, cultural and enterprise hub

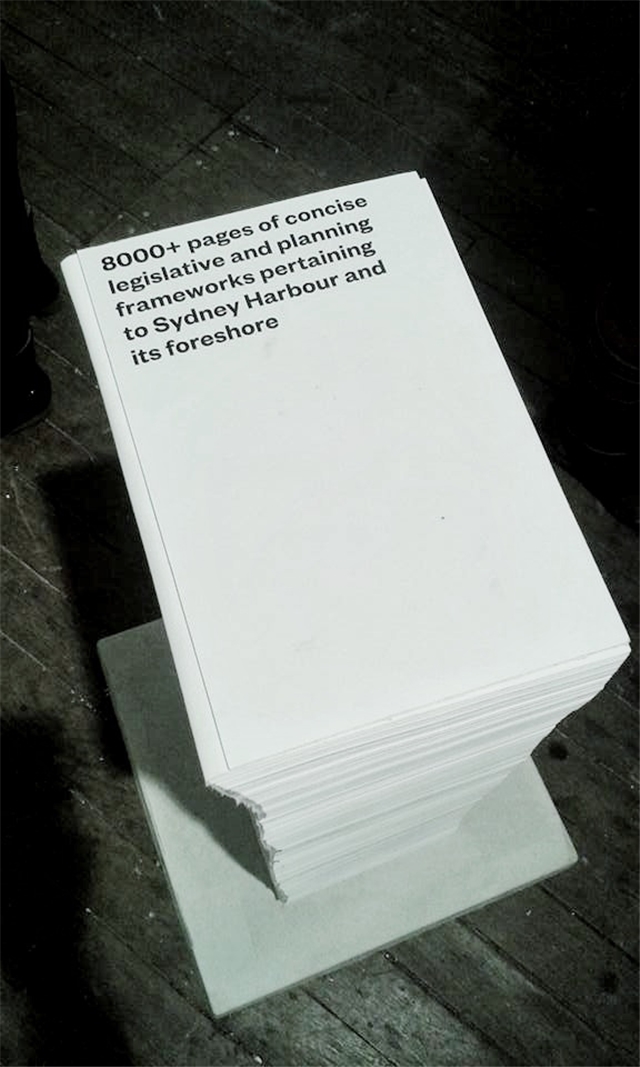

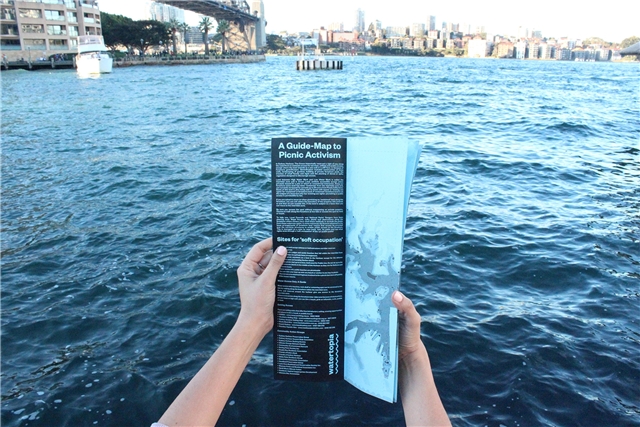

Picnic Activism

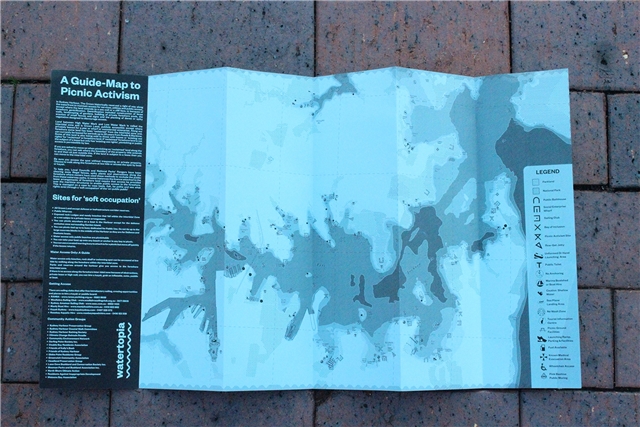

Structures built on public land without DA approval now continue to remain. Recent amendments and the addition of new sub-clauses allows property owners with currently unapproved private jetties to apply for 20 year leases using their ‘existing use rights’. It is designed to protect property value and exclusive use of foreshore lands. The smaller fine-grain battles are with individual property owners. They together make up long stretches of harbour foreshore impeding access with super yacht jetties, private swimming pools, small fences, landscaped gardens and security warnings. Small beaches only accessible by water, Rock shelves reavealed at low tide that are perfect for fishing, swimming holes once public and now with access cut off by land. These are our sites of picnic activism. Through a ‘soft occupation’ we want to challenge a culture of privilege and imagine a future of equitable and free access to the foreshore. We arm you with a Guide-Map to Picnic Activism that lists your rights, gives you locations and sets you free to reclaim the ‘un-public public’

Your pool is my pool

Along the foreshore of the harbour private swimming pools are commonly built on ‘reclaimed’* land, land which now due to ‘existing use rights’ can be leased for 20 years or purchased from Roads & Maritime.

An amendment to the Coastal Protection Act of 1979 concentrated on the issue of public access along foreshore areas and how redefining the position of mean high water will affect access rights. No longer does the theory of gradual and imperceptible change only apply to claims of accretion but now includes the assessment of indefinite sustainability, geomorphological processes and public access. Therefore, climate change based sea level rise would be the reduction in existing land title area of foreshore property owners. It would see the consumption of private foreshore land into public ownership.

Historically the harbour was a bathing paradise, at least before water quality decreased too significantly to allow swimming in the harbour a pleasure rather than a health hazard. Public bathhouses dotted the bays. These took the form of cut outs in the rock, or rocks being moved to further extend an existing natural protected swimming hole, some of which still remain or have been formalised such as the Clifton Garden Pool, and timber structures of various shapes and sizes with some shelter and change rooms, The Dawn Fraser swimming pool in Balmain and Red Leaf in Woollahra, the last remaining of these.

With improved water quality and the potential reclamation of private swimming pools into public ownership through climate change based sea level rise, we could again see the Harbour become a bathing paradise.

*’reclaimed’ land consists of levee walls and landscaped gardens built on and over public or crown land along the foreshore.