Si siglo XIX fue un siglo dedicado a los grandes edificios públicos -los teatros, las academias o los museos- la arquitectura durante el siglo XX dedicará sus esfuerzos al estudio de la casa. Todos los usos y tipologías se verán fuertemente revisados pero el núcleo de todos los esfuerzos y verdadero inicio de la arquitectura moderna será la vivienda. A partir de ella todos los preceptos modernos se irán aplicando a los distintos programas. Nikolaus Pevsner señala a William Morris como el primer arquitecto moderno porque precisamente entendió que un arte verdaderamente social, en consonancia con su tiempo y la sociedad a la que sirve, ha de ocuparse de aquello que preocupe a sus gentes.

Con la nueva situación de la vivienda en el centro de las motivaciones disciplinares el mueble adopta un nuevo protagonismo. En un momento avanzado de su carrera Marcel Breuer observa entre curioso e irónico cómo el mueble moderno había sido promocionado paradójicamente no por los diseñadores de muebles sino por los arquitectos[1]. La respuesta la da Le Corbusier en una de sus conferencias de 1931 recogida en Precisiones[2] cuando señala la reformulación del mobiliario como el "nudo gordiano" de cuya resolución pendía la renovación de la planta moderna. El Movimiento Moderno se había visto obligado de esta forma a atacar este tema para poder avanzar en sus propuestas domésticas.

La vanguardia arquitectónica se propuso solucionar los problemas de la vivienda y de una Europa en reconstrucción pero se exigía además ser capaz de aportar una visión propositiva de la vida moderna. No se trataba únicamente de resolver los problemas ya existentes sino que además había la necesidad autoimpuesta de anticipar la domesticidad del futuro. Para ello sus viviendas al completo, mueble e inmueble, debían de presentarse bajo esa nueva imagen. El manifiesto fundacional de la Deustcher Werkbund extendía el radio de acción del nuevo arquitecto desde la construcción de las ciudades a los cojines del sofá. Este mobiliario tenía la compleja misión de condensar sintéticamente todos esos ideales que la modernidad había traído consigo: abstracción, higienismo, fascinación maquínica, confianza positivista en la ciencia o la expresión material optimizada. Objetos de la vida moderna - en palabras de Le Corbusier- susceptibles de suscitar un estado de vida moderno.

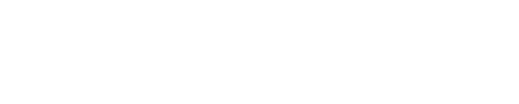

Pocas sillas en la historia del diseño habrán acarreado tanta polémica y tanta disputa por su autoría como la sillas voladas de tubo de acero en sus diferentes versiones. Para entenderlo situémonos en el año 1927 a las puertas de la exposición "Die Wohnung" ("La vivienda") organizada por los maestros de la Bauhaus y dirigida por Mies van der Rohe en la ladera Weissenhof de Stuttgart. Muchos nombres célebres de la arquitectura mostraron en esa ocasión su personal propuesta para la vivienda moderna y los objetos que la habitan. Entre ellos los muebles con tubo de acero fueron una presencia constante en la exposición pero hubo una pieza en particular que destacó sobre todas las demás por su novedad y audacia. La pieza en cuestión era el modelo de silla volada, esto es, sin apoyos posteriores y cuya rigidez estaba conferida al esfuerzo solidario de la estructura continua de tubo de acero y que terminaría por convertirse en el cruce de caminos de tres figuras de la disciplina arquitectónica: Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe y Mart Stam. Cada uno de ellos desarrolló su propio modelo de silla volada en sus versiones MR por parte de Mies, L&C Arnold de Stam y el posterior modelo BR 33 de Marcel Breuer. Los tres, en algún momento de su vida reclamaron de uno u otro modo su autoría como objetos que les pertenecían intelectualmente.

Estas sillas, que parecían flotar en el aire, se convirtieron en la expresión máxima de uno de los ansiados anhelos de la modernidad. La propia materialidad del acero, en su versión optimizada, era la que había derivado en una forma completamente nueva de un objeto cotidiano y cuyo tipo estaba ya totalmente asumido. Los nuevos materiales y las nuevas formas de hacer habían irrumpido hasta en los utensilios domésticos, y habían sido capaces de reformularlos.

El punto de partida para esta investigación es precisamente esa coincidencia de tres figuras de la arquitectura moderna, los tres de formación artesanal, en un mismo modelo de silla y en una misma fecha. Tres arquitectos que se habían encargado de asegurar que el movimiento moderno no reconocía problemas formales sino solamente de construcción, iban a coincidir en el mismo tiempo y lugar, precisamente en una misma forma, como si tal coincidencia hubiera sido producto de una voluntad de época. Sin embargo el interés de este estudio no radica en una indagación sobre la autoría sino sobre cómo un mismo objeto resulta ser propositivo e interesante en campos muy diversos y la forma en que cada uno lo hace suyo incorporándolo a su propia investigación proyectual. La silla, más allá de ser un objeto de diseño exclusivamente, trasciende su propia escala para situarse inmersa en un proceso de búsqueda y exploración a nivel conceptual, formal, constructivo y estructural en la arquitectura cada uno de ellos.

En un momento en que el oficio del arquitecto está siendo intensamente redefinido considero especialmente pertinente esta investigación, que en definitiva versa sobre la forma distintiva en que el pensamiento arquitectónico es capaz de proyectarse sobre cualquier disciplina para reformularla.

[1] "It is interesting that modern furniture was promoted not by the professional furniture designers, but by architects"

BLAKE, Peter. Marcel Breuer: Architect and Designer. Nueva York: Architectural Record/MoMA, 1949, p.25

[2] LE CORBUSIER. Precisiones respecto a un estado actual de la arquitectura y del urbanismo. Barcelona. Poseidón. 1978. p127