Leaping from numbers to people, to social concerns, is one of the architectural mediator’s overriding goals. The connection between architecture and politics cannot be understood without this professional, who - either from within the Administration or from the sidelines - is key to the development of big cities and handles copious budgetary flows of public monies.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan (Tulsa 1927- Washington 1993)

Daniel Patrick Moynihan adroitly maintained the trust of the American government for forty years, regardless of the party in power. Capable of “inventing” the commissions that interested him, he also fought to preserve historic buildings, in addition to putting forward his own ground-breaking proposals.

Moynihan's forte was his talent for making connections and getting projects on the boil within the cloud of bureaucracy. He had a knack for knowing which senator to ally himself with and which senior official’s door to knock on; above all, his objectives were clear. Convincing others was a matter of numbers and data, never ideology. It was enough for him to understand the economic formula by which politics is governed.

In 1962, the White House commissioned him to draft a report that would justify the construction of new public office buildings in Washington. The last buildings erected in the capital by the Federal Government – the so-called “gray buildings” – dated back to the 1930s; they were massive, gray and somber. In Moynihan’s opinion, they seemed “determined to impress upon citizens how unimportant they are”.

Moynihan’s Report to the President by the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space included the need to renovate Pennsylvania Avenue. The mediator considered that its image should be changed, more uses provided and even a zone with housing defined. Moynihan knew that such a massive project could not be tackled hastily and he even let deadlines expire so as to be able to keep redefining the project and shape it to his interests. The renovation of this emblematic avenue, comparable with the Champs Elysees in Paris, would take 40 years to complete.

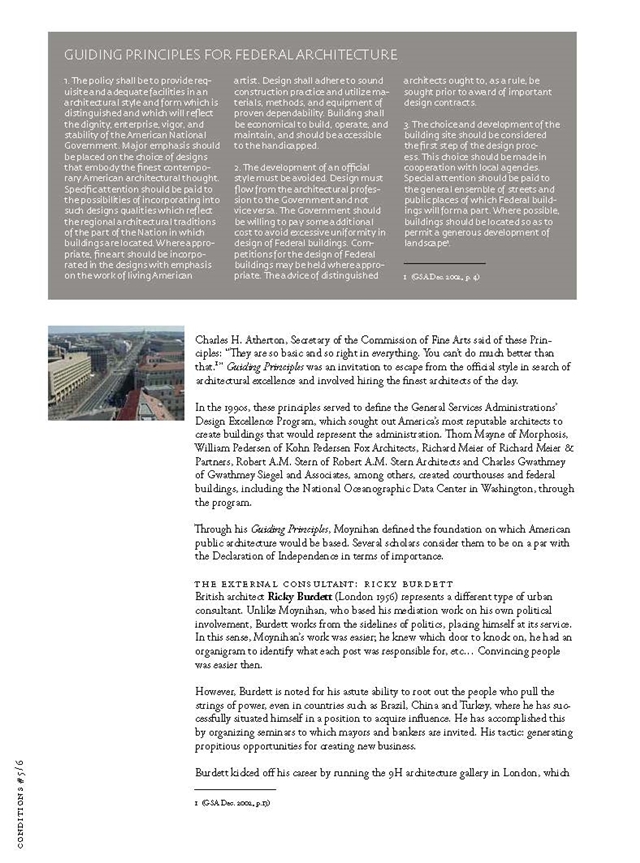

Together with the report, Moynihan presented his Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture, which over time became the guidelines for American public architecture.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR FEDERAL ARCHITECTURE

1. The policy shall be to provide requisite and adequate facilities in an architectural style and form which is distinguished and which will reflect the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American National Government. Major emphasis should be placed on the choice of designs that embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought. Specific attention should be paid to the possibilities of incorporating into such designs qualities which reflect the regional architectural traditions of the part of the Nation in which buildings are located. Where appropriate, fine art should be incorporated in the designs with emphasis on the work of living American artist. Design shall adhere to sound construction practice and utilize materials, methods, and equipment of proven dependability. Building shall be economical to build, operate, and maintain, and should be accessible to the handicapped.

2. The development of an official style must be avoided. Design must flow from the architectural profession to the Government and not vice versa. The Government should be willing to pay some additional cost to avoid excessive uniformity in design of Federal buildings. Competitions for the design of Federal buildings may be held where appropriate. The advice of distinguished architects ought to, as a rule, be sought prior to award of important design contracts.

3. The choice and development of the building site should be considered the first step of the design process. This choice should be made in cooperation with local agencies. Special attention should be paid to the general ensemble of streets and public places of which Federal buildings will form a part. Where possible, buildings should be located so as to permit a generous development of landscape

Vision+Voice, Design Excellence in Federal Architecture: Building a legacy (GSA, Dec. 2002), p. 4

Charles H. Atherton, Secretary of the Commission of Fine Arts said of these Principles: "They are so basic and so right in everything. You can’t do much better than that." Vision+Voice, Design Excellence in Federal Architecture: Building a legacy (GSA, Dec. 2002), p. 13. Guiding Principles was an invitation to escape from the official style in search of architectural excellence and involved hiring the finest architects of the day.

In the 1990s, these principles served to define the General Services Administrations’ Design Excellence Program, which sought out America’s most reputable architects to create buildings that would represent the administration. Thom Mayne of Morphosis, William Pedersen of Kohn Pedersen Fox Architects, Richard Meier of Richard Meier & Partners, Robert A.M. Stern of Robert A.M. Stern Architects and Charles Gwathmey of Gwathmey Siegel and Associates, among others, created courthouses and federal buildings, including the National Oceanographic Data Center in Washington, through the program.

Through his Guiding Principles, Moynihan defined the foundation on which American public architecture would be based. Several scholars consider them to be on a par with the Declaration of Independence in terms of importance.

The external consultant: Ricky Burdett

British architect Ricky Burdett (London 1956) represents a different type of urban consultant. Unlike Moynihan, who based his mediation work on his own political involvement, Burdett works from the sidelines of politics, placing himself at its service. In this sense, Moynihan’s work was easier. He knew which door to knock on; he had an organigram to identify what each post was responsible for, etc.. Convincing people was easier then.

However, Burdett is noted for his astute ability to root out the people who pull the strings of power, even in countries such as Brazil, China and Turkey, where he has successfully situated himself in a position to acquire influence. He has accomplished this by organizing seminars to which mayors and bankers are invited. His tactic: generating propitious opportunities for creating new business.

Burdett kicked off his career by running the 9H architecture gallery in London, which was launched as a result of the success of the specialized architectural journal of the same name and open to the public between 1986 and 1991. The gallery devoted itself to promoting continental European architects who were virtually unknown in London, some of the most outstanding of whom were Lily Reich & Eileen Gray, Álvaro Siza, Francesco Venezia, Eduardo Soto de Moura, Eduard Bru and Herzog & de Meuron.

The exhibitions 9H mounted were attended by architects, politicians, journalists and decision-makers. Thus, the gallery was Burdett’s accelerated apprenticeship in becoming a mediator, since it was a source of business contacts. In one exhibition, he forged a relationship with the American firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, which led to a two-year stint at the Chicago Institute for Architecture. Learning close up about the American Way of Life enabled Burdett to solidify ideas and generate the concept of the Architecture Foundation, an independent center for discussing architecture from a practical standpoint in a professionalized manner. In his desire to embrace civil society as a whole and provide a special place for cultural power, Burdett limited his professional colleagues to one-fourth of the number of seats on the board. He sought to bring together the country’s cultural and economic elite, since they are the ones who decide on a zone’s architecture in the end.

In 1992, the Architecture Foundation was consolidated with City Changes, an exhibition on the transformations London would be undergoing; it toured four different countries to widespread public acclaim. From his post as director, Burdett proved capable of anticipating problems and the potential reactions of the general public and sources of power. Once both were sounded, he managed to convince politicians of the best strategy to follow. They heeded him, because architecture translates into votes.

In 1993, Burdett became Architectural Adviser to the Tate Modern, which established his reputation as a mediator. He was largely responsible for deciding on the new Tate's location in an old power station set in the run-down neighborhood of North Southwark. The four million visitors this rehabilitated building receives each year attest to the sagacity of this choice of venue.

Based on the Tate’s success, Burdett became an advisor to the BBC, the mayor of London and even the mayor of Barcelona. In 1997, he resigned his post as Director of the Architecture Foundation and was signed by the London School of Economics. There he created a new department within the Faculty of Sociology - the LSE Cities Programme - which became the first design-based center in a school of social sciences. Mayors and urban planners eager for successful recipes to apply to their cities flocked to his classes.

In 2005, Burdett went one step further and created Urban Age, a more international and ambitious conference forum that goes beyond the sphere of London and takes on the world. The conferences are held in cities undergoing transformation that serve as examples for others: New York, the reinvented city; Shanghai and its booming growth; London, Burdett's own city and the one he knows best; Johannesburg, site of failed strategies; Mexico City, on the verge of collapse; and Berlin, with its declining population. Burdett brings to the table what works and what does not and encourages his students and researchers to find solutions.

Urban Age allows Burdett to be a global consultant, although he wields influence, not direct power, a situation similar to Moynihan’s when he was Ambassador to the United Nations before becoming a senator from New York. He could influence many countries, but enjoyed no real power. Until he was elected senator, the keys to the vault were not his.

Today Ricky Burdett is immersed in this duality. On the one hand, he influences many countries as a consultant with Urban Age. On the other, he is beginning to have access to power in London.

Burdett is the “principal design adviser” for the 2012 London Olympics, a post that consists of hiring design teams, supervising construction works and ensuring tight budgets and works that are delivered on time. In some ways, it is the same work he did for the Tate Modern, but on a scale some 20 or 30 times larger. Now the budget is bigger, there are more sites and the country’s stakes in making itself known to the world and positioning itself are higher.

Burdett must organize, choose and establish selection criteria. In his way, he has created his own Guiding Principles, like Moynihan’s:

“1) Firstly, the brief will always put design on an extremely high threshold, alongside deliverability and functionality. 2) We then go out and find the very best talent available for the job, regardless of profile. 3) Finally, we have mechanism in-house that ensure design quality is always balanced with restrictions such as time and budget” Let the games begin. Designbuild (Phin Foster, 1 Aug. 2007)

As a politician, like Moynihan, or as a consultant, like Burdett, the architectural mediator is an indispensable figure in urban development. Politicians, developers and architects need them to achieve coherent and functional urban growth that benefits citizens.

“Architects shape cities. Politicians make policies. Getting them to talk to each other is what interests me”. Brief encounter: Ricky Burdett. (Riba Journal v.112, Sept. 2005)

The words are Burdett’s, yet the great Moynihan would surely agree.