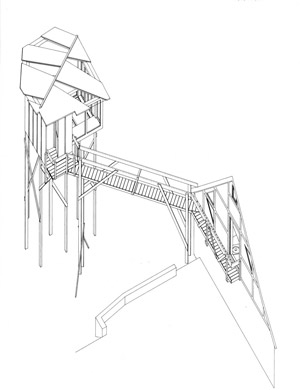

'The room to keep the witch's broom'

Alison Smithson was given the fascinating task of creating a witch's broom room by Axel Bruchhäuser. To do this, he created a small cabin sitting on pillars next to the treetops that rest, in turn, on a slight slope that descends to the river crossed by a bridge from the witch's house. Its tiny interior is designed to see the river, the house from behind, look down and see the forest floor, and look up and see the canopy formed by the leaves and the sky.

Although unfortunately in many cases reality takes care of denying it, the exercise of architecture is not understood if it is not to contribute to the construction of a preferable world. In order to carry out this commitment, we must set a creative process in motion for each project, so we can move from intentions to reality, being able to acquire a solution in this complex journey, an important work emerging as a result.

To great extent, reaching a better world is not viable without reflection and, in order to carry it out, it is necessary to distance oneself from reality in order to understand it, since if only the close look is exercised, one ends up paying attention exclusively to the particular. However, the further we move away, the loss of detail allows us to perceive the existence of an invisible and diffuse structure that supports our proposals. If we continue to distance ourselves, we have the feeling that this frame is also part of an even more abstract and intangible skeleton. Accessing these enclaves, even if only for an instant, means entering an imprecise and unfocused universe in which time and the specific features of each place are diluted. It is probably in these diffuse spaces where we come to recognize the attitudes and proposals of others and discover affinities invisibles to a closer look, even more, I would say that, due to their indetermination, they are suitable to ask themselves the questions and to acquire the commitments that have to guide our decisions.

Making a space for reflection is not easy in the culture of immediacy in which we are immersed, but to achieve it means giving oneself the opportunity to open a window to the unknown, to the immensity that, as Gaston Bachelard reminds us in his book The Poetics of Space, it "inhabits within us", "is linked to a kind of expansion of being that life represses and caution stops, but that starts again when we are alone. As soon as we are immobilized, we are somewhere else; we are dreaming of a world that is immense. Immensity is the movement of the immobile man".

Pressed by the excess of noise and information, it is vital to have a protective shelter which is an indispensable requirement for the patient search. If this search is necessary, and in my opinion it is, what should the ideal space for thought be like, that stronghold of maximum freedom from which we project ourselves outwards? What should that shelter be like so that it provides the necessary tranquillity to think about a more just and supportive world and, as a consequence, transform it into a more habitable place?

I do not intend to forget the other shelters, those that press on us every time there is famine, war or natural disasters, and which we often forget about as soon as they are no longer in the news, but only through the former is it possible to give the adequate response that the latter demands.

Antonello da Messina designed one of these places to accommodate Saint Jerome, Father of the Church and translator of the Bible into Latin. Jules Verne proposed it to us in De la terre à la lune, Alvar Aalto built Nemo propheta in patria with a similar intention and Le Corbusier spent the last days of his life in the paradigmatic Cabanon. They all have in common their smallness, and probably this made Alison Smithson open her window, that of the room to keep the witch's broom, to the immensity of the forest, Antonello da Messina to the immensity of the refined Italian landscape, Alvar Aalto to the immensity of the Finnish lakes, Le Corbusier to the immensity of the Marenostrum, and Jules Verne to the most overwhelming immensity of all, that of the infinite universe.

Purpose of work

A minimum shelter is the most humane architecture precisely because of this condition of body protection and intimacy, with the needs of rest, hygiene and food resolved.

Location

That which they deem fit. It can be real or virtual, figurative or abstract, but in both cases the choice must be justified.